Problem of Monkey Coding

Back when I first started my first big java project (2000 lines of code), I just started coding like a monkey without caring about the design beforehand. I paid the price since:

- I didn’t really think about what was the core problem I was trying to solve.

- Every class was entangled to each other like spaghetti. Adding new features was getting harder and harder, commit after commit. Today I want to talk about domain driven design and how this methodology helps you design your big project like a chad

Goal

DDD is all about bridging the gap between software experts (us devs) and domain experts (the folks who live the problem—like bankers in a banking system). A domain is just the problem space you’re tackling with your code. The goal? Better collaboration, less misunderstanding, and a product that actually solves the right problem. Plus, it’s a killer way to figure out where your microservices should live.

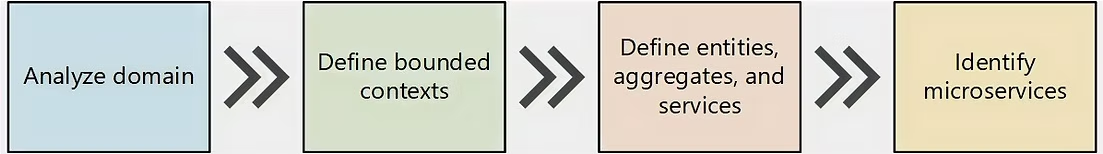

How DDD Works: The Steps

1) Strategic DDD

This is the big-picture stuff—getting everyone on the same page:

- Develop a Ubiquitous Language: A shared vocab devs and domain experts both get.

- Define Scope (Bounded Context): Draw lines around what you’re building.

- Create Subdomains: Break it into smaller, focused chunks.

- Build a Domain Model: Map out the key concepts and rules.

- Event Storming: Brainstorm the business flow with the team.

- Repeat: Keep refining—it’s not a one-and-done deal.

2) Tactical DDD

Now, turn that model into code:

- Entity Object: Things with identity, like a financial transaction (e.g., withdrawing $20 from an ATM).

- Value Object: Immutable stuff with no identity, like the date of that transaction.

- Aggregate: A cluster of entities and values that work together.

- Service: Logic that operates on entities and values.

- Repositories: Where entities get stored and fetched.

Ubiquitous Language

Imagine devs and bankers agreeing on what “transaction” means—no tech jargon, no finance buzzwords, just clear terms. That’s the ubiquitous language: a common tongue so misunderstandings don’t tank the project. In a banking system, “balance” might mean one thing to coders and another to tellers—DDD makes sure it’s the same.

Iterative Collaboration

Complex logic doesn’t sort itself out in one meeting. Designing the domain model takes multiple sessions—talking, tweaking, and aligning with domain experts. It’s like sculpting: chip away until it fits the real world.

Bounded Context

What It Is

Bounded Contexts are your design’s boundaries—subdomains that let you focus on one piece at a time without drowning in the whole mess. Each has its own model and language.

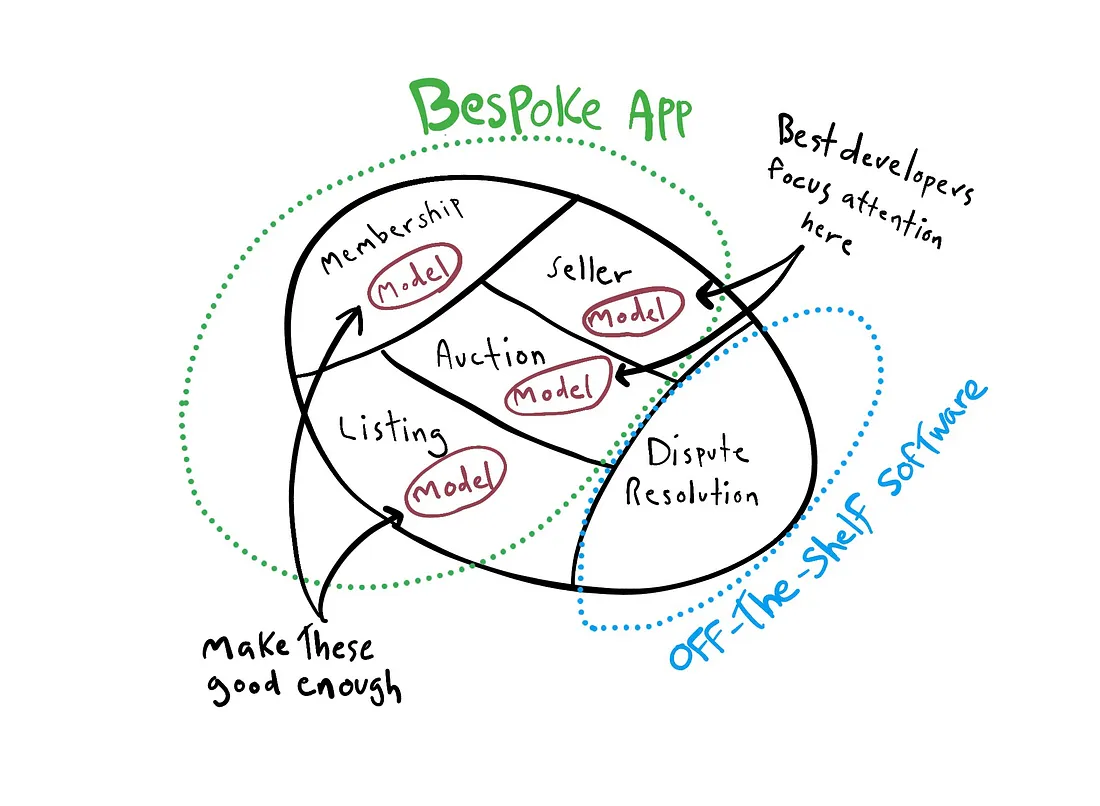

Core Subdomain

The heart of your product—what makes it stand out.

- Example: Payments and Transactions in a banking system. Fast, reliable, affordable transfers are why customers pick you over the competition. Focus your best effort here.

Supporting Subdomain

Stuff that helps the core but isn’t the star.

- Example: Customer Management. Authentication, profiles, UI—vital, but not what wins the race. Build it solid, not flashy.

Generic Subdomain

Features every player has—don’t reinvent the wheel.

- Example: Regulatory Compliance. Anti-money laundering, audits—use off-the-shelf tools since it’s the same everywhere.

Event Storming

This is where devs and domain experts huddle up, grab some sticky notes, and map the business logic. Picture a timeline: “Customer deposits cash” (event) → “System updates balance” (command). It helps spot bounded contexts and ends with a Context Map—a UML-ish network of microservices.

- Too Big?: If the map’s a monster, your subdomains need splitting.

- Key Bits: Domain Events, Commands, Actors, Aggregates, Views.

Real-World Example: Banking System

Say a customer deposits $100:

- Payments and Transactions (core) updates the balance and logs the deposit.

- Customer Management (supporting) verifies their account.

- Regulatory Compliance (generic) checks if it’s fishy.

Each context does its job, talks when needed, and stays clean.

Use Cases

DDD shines in big projects with gnarly business logic—tons of edge cases and details.

- Examples: Banking (SWIFT compliance, anti-money laundering), ERP systems.

Misuse Cases

Don’t bother with DDD for:

- Small-to-medium projects—too much overhead.

- Technical projects where the dev is the domain expert (e.g., a web browser or Linux’s 27M lines of OS code). No point talking to yourself.

Benefits

- Separation of Concerns: Smaller contexts = easier focus.

- Flexibility: Each service has one job—open to extend, closed to mess-ups.

- Product-Minded Devs: Chatting with experts fills gaps and sharpens decisions.

- Maintainability: Teams own domains, speeding up dev and taming complexity.

Drawbacks

- Extra Complexity: Overkill for simple apps—just YAGNI.

- Steep Learning Curve: More complexity, more time (and cash) to grok it.

Microservices and DDD

DDD comes first: define subdomains, map their relationships, then build each as a microservice. It’s the blueprint before the construction.

Other Topics to Ponder

- Strategic vs. Tactical DDD

- Tactical Patterns’ Use Cases

- Does Event Storming Use UML?

- Storytelling vs. Event Storming

- Event Storming in Action

Conclusion

At its heart, DDD is about knowing your customer’s problems—and building software that actually solves them. It’s not just fancy words; it’s a mindset shift from monkey-coding to chad-designing. Next time you’re starting a project, grab a domain expert, sketch a bounded context, and see how it changes your game.