Introduction

Imagine you’re building an e-commerce platform with a microservices architecture. Your system is split into independent services:

- Order + order database

- Payment + payment database

- Inventory + inventory database

- Shipping + shipping database

A customer places an order, and you need to ensure the payment is processed, inventory is reserved, and shipping is scheduled—all in one smooth flow.

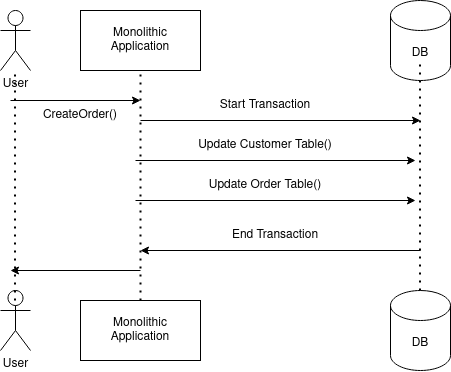

In a traditional monolithic application, you’d wrap this in a single database transaction:

If anything fails, the transaction rolls back, and consistency is preserved. Easy, right?

But in a microservices world, there’s no single database to lean on:

Each service operates in isolation, and coordinating them feels like herding cats. You could try a distributed transaction using something like two-phase commit (2PC), but that quickly becomes a bottleneck—locking resources across services, slowing down performance, and crumbling under failure scenarios.

What happens if the Inventory service crashes after Payment succeeds? You’re left with an inconsistent mess: money taken, but no goods reserved. This is the distributed consistency problem: how do you ensure data integrity across independent services without sacrificing scalability or availability?

Enter the Saga design pattern—a lifeline for microservices architects tackling this very challenge.

The Saga Pattern: A Solution for Distributed Workflows

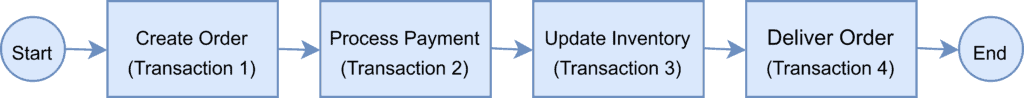

The Saga pattern offers a way to manage complex, multi-step operations across microservices without relying on a centralized transaction manager. Instead of enforcing immediate consistency with locks, it breaks the process into a series of local transactions, each handled by a single service. If something goes wrong, compensating actions undo the previous steps, ensuring eventual consistency.

Think of a Saga as a story: each chapter (or step) moves the plot forward, but if the ending flops, you can rewrite the earlier chapters to fix it. There are two flavors:

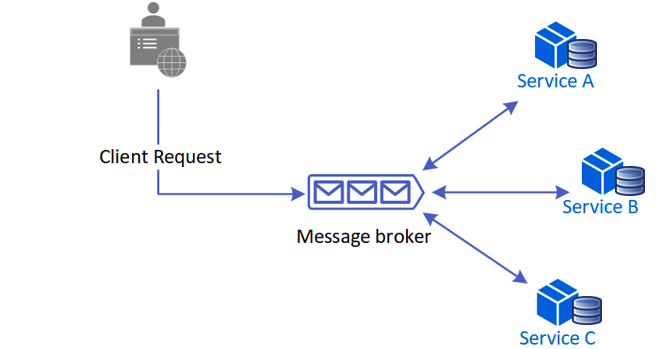

Choreography: Services communicate via message brokers such as a queue. Each service listens for an event, does its job, and triggers the next event.

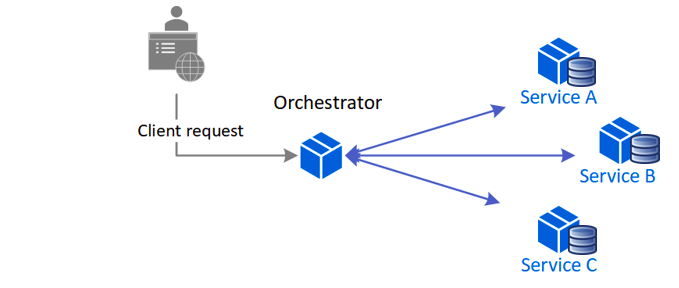

Orchestration: A central coordinator directs the services, telling each one what to do and when—like a conductor leading an orchestra.

For our e-commerce example, a Saga ensures the order process either completes fully or unwinds gracefully if a step fails, avoiding the dreaded inconsistent state.

Implementing the Saga Pattern in Pure Java

Let’s implement an orchestrated Saga in Java for our e-commerce scenario. We’ll keep it simple to focus on the core concepts.

Step 1: Define the Saga Orchestrator

The orchestrator manages the workflow and handles rollbacks.

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

public class OrderSagaOrchestrator {

private List<SagaStep> steps = new ArrayList<>();

private List<SagaStep> executedSteps = new ArrayList<>();

public void addStep(SagaStep step) {

steps.add(step);

}

public void execute(Order order) {

try {

for (SagaStep step : steps) {

step.execute(order);

executedSteps.add(step);

}

System.out.println("Order processed: " + order);

} catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println("Saga failed: " + e.getMessage());

rollback();

}

}

private void rollback() {

for (int i = executedSteps.size() - 1; i >= 0; i--) {

executedSteps.get(i).compensate();

}

}

}

Step 2: Create the SagaStep Interface

Each service implements this interface with an execute method for the action and a compensate method for the rollback.

public interface SagaStep {

void execute(Order order) throws Exception;

void compensate();

}

Step 3: Implement the Steps

Here’s how the Payment and Inventory services might look.

Payment Step:

public class ProcessPaymentStep implements SagaStep {

@Override

public void execute(Order order) throws Exception {

System.out.println("Processing payment for " + order);

if (order.getAmount() > 1000) { // Simulate failure

throw new Exception("Payment failed: Amount too high");

}

order.setStatus("PAID");

}

@Override

public void compensate() {

System.out.println("Compensating: Refunding payment");

}

}

Inventory Step:

public class ReserveInventoryStep implements SagaStep {

@Override

public void execute(Order order) throws Exception {

System.out.println("Reserving inventory for " + order);

order.setStatus("INVENTORY_RESERVED");

}

@Override

public void compensate() {

System.out.println("Compensating: Releasing inventory");

}

}

Step 4: Define the Order Model

A simple class to hold order data.

public class Order {

private String id;

private double amount;

private String status;

public Order(String id, double amount) {

this.id = id;

this.amount = amount;

}

public void setStatus(String status) {

this.status = status;

}

public double getAmount() {

return amount;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return "Order{id='" + id + "', amount=" + amount + ", status='" + status + "'}";

}

}

Step 5: Run the Saga

Tie it together in a main method.

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

OrderSagaOrchestrator saga = new OrderSagaOrchestrator();

saga.addStep(new ProcessPaymentStep());

saga.addStep(new ReserveInventoryStep());

// Failing case

Order order1 = new Order("123", 1500);

saga.execute(order1);

System.out.println("\n---\n");

// Successful case

Order order2 = new Order("124", 500);

saga.execute(order2);

}

}

Output (payment failure) :

Processing payment for Order{id='123', amount=1500.0, status='null'}

Saga failed: Payment failed: Amount too high

Compensating: Refunding payment

Output (No failure):

Processing payment for Order{id='124', amount=500.0, status='null'}

Reserving inventory for Order{id='124', amount=500.0, status='PAID'}

Order processed: Order{id='124', amount=500.0, status='INVENTORY_RESERVED'}

This basic implementation shows how a Saga coordinates steps and compensates for failures. In a real system, you’d use a message broker (e.g., Kafka) for communication and persist the Saga state for recovery.

Frameworks That Support Saga

While you can roll your own Saga (as above), frameworks can simplify the heavy lifting:

- Axon Framework: A Java-based CQRS and event-sourcing framework with built-in Saga support. You annotate a class with @Saga, and it handles event-driven workflows automatically. Axon manages state and event routing, making it ideal for complex systems.

@Saga

public class OrderSaga {

@StartSaga

@SagaEventHandler(associationProperty = "orderId")

public void handle(OrderCreatedEvent event) {

// Trigger next step

}

}

- Spring Boot with Spring Cloud Stream: Combine Spring Boot with a message broker (Kafka, RabbitMQ) for event-driven choreography. Spring Cloud Stream abstracts the messaging layer, letting services publish and subscribe to events.

- Camunda: A workflow engine that supports orchestrated SAGAs via BPMN processes. It’s great for visual workflow design and execution.

- Eventuate Tram: A lightweight framework for SAGAs in Java, supporting both choreography and orchestration with messaging backends like Kafka or ActiveMQ.

These tools reduce boilerplate, handle retries, and integrate with distributed tracing—crucial for production-grade microservices.

Saga vs. Two-Phase Commit (2PC)

The Saga pattern often gets compared to the two-phase commit (2PC) pattern, a traditional approach to distributed transactions. Let’s break it down:

| Aspect | Saga | Two-Phase Commit (2PC) |

|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Eventual consistency | Immediate consistency (ACID) |

| Mechanism | Local transactions + compensations | Two phases: prepare and commit |

| Coordination | Decentralized (choreography) or lightweight orchestrator | Centralized coordinator |

| Scalability | High—avoids locks, scales horizontally | Low—locks resources, bottlenecks |

| Failure Handling | Compensating actions on failure | Rolls back if any participant fails |

| Complexity | Higher—requires compensation logic | Lower—handled by transaction manager |

| Performance | Fast—local commits, no waiting | Slow—requires all parties to agree |

| Use Case | Microservices, distributed systems | Traditional distributed databases |

Key Differences

Locking: 2PC locks resources across all participants during the prepare phase, waiting for everyone to agree before committing. Saga avoids locks by committing locally and compensating later if needed.

Failure Tolerance: If a 2PC participant fails during the commit phase, the whole transaction aborts. Saga handles failures gracefully with compensations, keeping the system moving.

Scalability: 2PC struggles in high-throughput systems due to its synchronous nature. Saga’s asynchronous, decoupled approach shines in cloud-native setups.

Failure handling: Rollbacks need a locking mechanism. We lock an operation till we commit the transaction. Meanwhile it is locked, we can roll back the transaction. Once the transaction is commited, you can’t roll back it. That’s when compensation comes in. You neutralise the effect of the transaction by another transaction.

When to Choose

Use 2PC when you need strict ACID guarantees and operate in a controlled environment (e.g., a single RDBMS cluster). It’s overkill for microservices.

Use Saga when building resilient, scalable microservices where availability trumps immediate consistency—think e-commerce, booking systems, or any distributed workflow.

When Not to use Saga

- There are circular dependencies between your services. Transaction compensation enters an infinite loop.

- You need to ensure immediate consistency. Saga pattern provides eventual consistency. A transaction is not complete in some services. Transaction eventually becomes consistent after going through all services.

- Example: financial systems such as banks

- Your app is monolithic. All steps are done in a single service and use single database

- When latency and performance are critical. Compensation is slower than doing rollbacks